Previous Parts: Part I Part II

Recap: The Church is complicated because it is the company of God's eternally elect, but it is also a family. When we think of the church as God's bride, we think in terms of purity and personal possession of salvation. The church defined in this way cannot be seen by human eye. But when we think of the church as a family and as the means by which God brings the Gospel to the nations, we are thinking of the Church as it functions in space and time. We therefore have a problem of knowledge as we approach the church: Who properly belongs to it?

This problem cannot be solved by a simple appeal to election. While it is true that God accepts only His children as genuine members of his body into eternity, our lack of "election-o-meters" prevents us from applying election as an operational test for church membership.

Nor can the problem of knowledge be solved by a simple appeal to outward profession of faith. The Scriptures make clear that not all who name Jesus as Lord actually know Him as such.

Further, it appears to be God's plan to leave this tension unresolved on this side of eternity. The parable of the Wheat and Tares suggests that God leaves tares within the church until his appointed time1. And the fact that family members of Christians are considered "holy" -- even if unsaved (1 Cor 7.12-14) eliminates the possibility of defining the church cleanly as "those who possess saving faith."

And yet, the Church is Christ's body; we must affirm that unbelievers do not properly belong to it. It is for this reason that Paul urges the Corinthians to "expel the wicked man from among you."

How then are we to understand the church? Whom should we consider as belonging to the church?

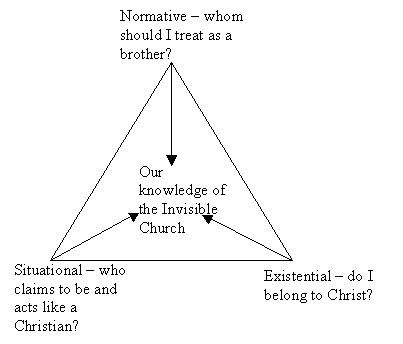

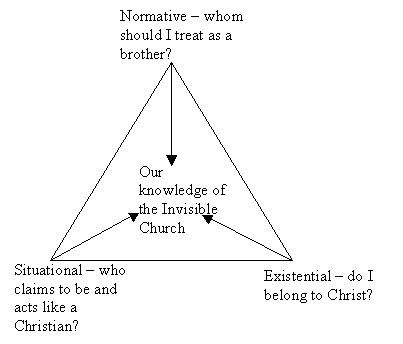

I contend here that the problem of knowing the church only admits of partial solutions viewed from different perspectives2. In the final analysis, we do not have access to God's decrees, and we cannot see the Church as God sees it. What we have instead is several different Scripturally mandated ways of measuring the Church approximately.

If we ask, "To whom do we owe an obligation to treat as a brother in Christ?", we are asking a normative question. The answer to that question describes a set of people whom we may call "the Church"; we are measuring the Church by the yardstick of ethical obligations that naturally exist by virtue of belonging to Christ's family.

Yet we recognize that the members of this set of people do not necessarily possess salvation, so that the Church as measured by ethical obligations does not correspond perfectly to the Church as God sees it. So we might ask a second question: "Who displays the fruit of belonging to Christ?" This fruit might include outward professions of faith as well as visible demonstrations of the fruit of the Spirit. The answer to that question also describes a (different) set of people whom we may call Christians -- Christ's people. We are measuring the Church according to visible observation of their fruit.

And yet again, we recognize that some who have the appearance of Christ's followers can yet be in unbelief, while some who belong to Christ can sin grievously for a time. Thus, the Church as measured by visible observation of fruit still does not correspond perfectly to the Church as God sees it. In particular, many struggle concerning themselves: do I belong to the Church? So each individual must consider a third question, "Do I believe the Gospel and trust in Christ?" Here each man measures himself in relationship to the Church by discerning whether he legitimately belongs to it.

Now two things should be clear from the outset. First, none of these metrics is fool-proof. The Scriptures insist that people can belong to the Church visibly, or display a kind of false fruit of salvation (cf. 1 Cor 13), or imagine themselves to be saved, and yet fail to truly belong to Christ's people (Matt. 7.22).

But second, none of these metrics can be disposed of. Because our view of the Church is limited, it can be tempting to grab on to one of these perspectives as "the way" to see the church. Hence, the Roman Catholics view the Church almost entirely through the normative perspective; modern evangelicals, through the existential. Yet Scripture pushes us to admit that none of these perspectives is so dispositive as to preclude the others.

So our task, then, is to consider three different ways of measuring the Church: a "tri-perspectival" view of the Church. None is sufficient by itself; but each can be found in the Scriptures at various points.

The Normative Perspective

Here we ask the question, "Whom should I treat as a member of the Church?" The Scripture demands this question at several points:

1. Hebrews 13.1 exhorts us to "Keep on loving each other as brothers." And again, Gal. 6.10 tells us to "do good to all people, and especially to those who are of the household of the faith."

Now the question becomes, whom must we treat in this way? That is, as I consider my special obligation to do good to the household of faith, whom should I treat in this way?

And the answer is clearly, those who visibly profess Christ and belong to His Church. From the perspective of my obligations, if only to err on the side of caution, I must treat all who profess Christ as if they are legitimately a part of Christ's people.

In other words, the normative perspective on the Church leads us to define the Church in terms of a visible boundary: visible church membership. No other answer to the question will do. I could not, for example, choose to not love Alice on the grounds that her behavior "proves she is not a Christian"; without the warrant of formal excommunication, such an action amounts to the hand rejecting the foot.

2. Hebrews 13.17 exhorts us, "Obey your leaders and submit to them, for they keep watch over your souls as those who will give an account."

To whom must I submit? To the leaders of my church. Here, the normative perspective leads us again to define the church in terms of its visible leadership. I cannot (unless I leave the church) choose which elders I will submit to and which I will disregard.

3. 1 Cor 7.12-14 asserts that the children of believers are "holy." In what sense? Certainly, all agree that children of believers are not automatically saved, nor automatically sanctified from within. But they are holy, "set apart", in this sense: they have a special obligation above those outside the church to believe and obey the Gospel. To whom more is given, more is required.

They are normatively holy, people who ought to be and have every reason to be Christians even if they are not.

So from the normative perspective, we get a strong sense of the "family" and "government" character of the Church. From this perspective the Church includes some who might not be actually saved: false brethren, false leaders, apostate children. Those people do not have a real right to belong to God's fellowship, and yet God in His providence leaves them in place until such time as He chooses to cut them off.

We, on the other hand, must err on the side of caution with regard to their membership, because we are not wiser than God and because we have no direct knowledge of the salvation of individuals.

The Situational Perspective

We do, however, have the ability to read the actions of professing believers and measure them for two purposes: avoiding false teachers, and exercising church discipline. This perspective is called the "situational" in that it assesses the observable situation. It measures the church according to what we can see.

If we used only the normative perspective to measure the church, we would wrongly allow unbelief to persist within the church. While God's providence is ultimately sufficient to deal with this, He has also commanded us to measure the lives of others in limited ways in order to preserve the purity of the Church.

1. In Matt. 7, Jesus positively commands his followers to avoid false teachers, telling them, "Beware of the false prophets, who come to you in sheep's clothing, but inwardly are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Grapes are not gathered from thorn bushes nor figs from thistles, are they? So every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot produce bad fruit, nor can a bad tree produce good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. So then, you will know them by their fruits. Not everyone who says to Me, 'Lord, Lord,' will enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of My Father who is in heaven will enter. Many will say to Me on that day, 'Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in Your name, and in Your name cast out demons, and in Your name perform many miracles?' And then I will declare to them, 'I never knew you; depart from me, you who practice lawlessness.' -- Matt. 7.15-23 NASB

2. Likewise, 1 Cor 5 enjoins the church leadership to expel self-named Christians who unrepentantly practice lawlessness.

Here, the situational perspective refines the normative perspective: we owe love to church members and submission to church leaders, but that love and submission are not so absolute that we blindly accept their every action as legitimate.

Thus, we get a sense of how the two perspectives can combine in cases of church discipline: the behavior of the believer is weighed specifically by the church leadership, who are then given the authority to require repentance (on the basis of an individual's church membership) and in extremis to pronounce an individual outside the normative boundary of the church: that is, to excommunicate.

The Existential Perspective

In addition to assessing our ethical obligations to others and to observing the fruit of other believers, the Scriptures also tell us to assess ourselves.

1. As Paul wrestles with the Corinthians concerning their following of false teachers and questioning of his authority, he turns the tables and commands them, "Examine yourselves to see whether you are in the faith" (2 Cor 13.6).

This self-examination brings out what could be called the existential perspective. It asks each individual to assess who he is in relationship to the Church: Do I belong? Do I believe in Christ?

Self-examination is enjoined or implied in various passages. Sometimes, it is more internally focused, as 2 Cor 13.6 above, or as Jesus insinuates to Nicodemus in John 3 ("You are the teacher of Israel, yet you do not understand these things?"). Sometimes, it is externally focused. James 2, for example, brings the reader to the point of self-examination with regard to his own works and their consistency with professed faith.

From this perspective, each individual bears responsibility for knowing whether or not he is a part of the Church.

Interaction between Perspectives

Many of the common functions of church government show interactions between the perspectives. For example, church discipline begins with an assessment of the outward behavior of the individual, with a goal towards self-assessment by the individual (leading hopefully to repentance). In the extreme, that individual may be declared normatively to be outside the Church.

We see in church discipline the various perspectives at work, while recognizing that none of them is a perfect measure of who properly belongs to the church -- saved individuals can be wrongly excommunicated; unsaved individuals can be overlooked by church leadership.

The practice of communion also combines the various perspectives. With whom should we partake communion? With all who belong to the Church visibly. But as we partake, we are also asked to examine ourselves and to reaffirm that we, partaking of the one loaf, also belong to Christ's body.

Likewise, our assurance that we belong to Christ draws on each of these perspectives. Clearly, there is a large existential component here; it may indeed be so strong as to constitute what the Confession calls an "infallible certainty." And yet, we also take comfort from the evidence of the fruit of the Spirit in us (situation) and also from the claim made on us by baptism (normative).

Correspondence with the Confession

Some might wonder how well the tri-perspectival view of the Church corresponds to the picture given in the Westminster Confession, since tri-perspectival language is, superficially, very different from the language of the WCoF.

The three perspectives taken together -- especially the normative -- correspond to the Visible Church of 25.2 and 3. Sections 25.4-5 correspond to the problem of knowledge; we use the practices of any given Church to try to discern whether it is legitimately a part of God's Church.

Ch. 26 ("The Communion of the Saints") corresponds strongly to the normative perspective, while 27-30 (Sacraments and Church Censures) combine all three. The question of Assurance in ch. 18 addresses the existential perspective.

In other words, the tri-perspectival model attempts to reorganize our Confessional approach to the Church without modification (at all!) of the Confessional content.

Why re-organize, then? Most importantly, our tri-perspectival model demonstrates the unity between the Visible and Invisible Church. The two are not separate entities; rather, the Visible Church *is* the Church -- as far as we can see. It has the right to the name of Christ. But also, the Visible Church consists of our perspectives; therefore, it does not have an absolute right to the name of Christ. Its boundary is an imperfect approximation of the boundary of God's elect.

This is entirely in harmony with the Confession. However, it prevents one important misconception. As John Murray noted3, the language of the Confession can sometimes lead some to a wrong belief that the visible and invisible churches are two separate entities. Not so: rather, the Visible Church is our way of knowing the true, Invisible Church of God.

The Bidirectional Nature of the Perspectives

Thus far, we've seen the three perspectives as three legitimate but imperfect ways to reach behind the veil and perceive God's Church. But as it turns out, the three perspectives also correspond to the ways in which God communicates the gospel to the lost.

Normatively, the Church has the authority to preach the Gospel and to declare the boundaries of heresy. In the end, how can we know that those nice Mormons who "believe in Jesus" are nevertheless not Christians? Because they reject the testimony of the Church as expressed in the Nicene Creed -- which in turn rests on good and necessary inference from Scripture.

Situationally, God communicates the gospel through the actions and relationships of its members. "By this", says Jesus in John 13.35, "all men will know that you are my disciples: that you love one another."

Existentially, the work of the Spirit, which normally comes through the preached Word and administered Sacraments, convicts men of sin and their need for repentance.

Thus, the Visible Church is not merely a concept needed to solve our problem of knowledge. It does indeed function in that way, but moreover, the Visible Church is the functioning of God's Church in the here and now.

Thus, we have two ways of thinking about the Visible Church:

(1) The Visible Church is our best view of God's true and Invisible Church, refined by means of the various perspectives.

(2) The Visible Church is the family of God in the here-and-now, authorized to act as God's Church in the proclamation of the Word and the administration of the Sacraments.

JRC

1. Sometimes it is argued that the designation of the field as "the world" in Matt. 13.38 precludes thinking of the Tares as members of the church. But this argument strains at gnats. The point of the parable is that the wheat and tares are indistinguishable until they bear fruit -- which could hardly be the case if the wheat were all within the church and the tares without!

2. Here I will be drawing on the perspectivalism of John Frame. See here and here, as well as Frame's Doctrine of the Knowledge of God.

3. John Murray, Christian Baptism, Chap. 3.

Read more...

The lighting here was dim, but this shot captures the hairstreak in characteristic behavior: rubbing the hindwings together. A peek of the brilliant blue hindwing top is just visible.